”Unique as oppressed in that there is no other measure, they spoil for wars now; petty kingdoms to fight over, giving but tokens of brotherhood; sessing their folk into unfed bond-slavery—no measure. The Irish Catholic is twisted by shallow cause while feeding their Tanist bulldogs—no other measure.” Unknown journalist.

From gushing ink, the stories bleed of Dubliners plotting in silence and a formidable fate donned in the red coat. King’s white horses high-step along filthy cobbles; invaders that steal Ireland’s treasures, who look down a pugnacious nose at ‘a sub-species’ while Jackeens embolden their weak family names. Killing an Irish Catholic is a misdemeanour, marrying one a capital crime. And thus, the seeds of duplicitous disobedience, long sown, sprout deep roots across the pond. Stories drift home about edification from agrarian to rebel; ramshackle to regiment; pitiful to proud. Redcoats lay dead on their faces, the drums sounding, pipes playing songs celebrating the King’s dripping red dye.

In London, from whence Ireland’s fate is steered, constitutional assuages remain as hollow as twelve pounders. And still, no Catholic is legally permitted in parliamentary debates. Finally, more the English laws for that voteless majority, lights a Romish touch-paper: pitchforks in shaking hands. Farmers turn their calloused fists to piling spiked poles beneath bales of hay. Dexterity lacking, others take up rusting flintlocks, led by men of exceptional character, all resolute, if they should be made an example of; shoulder to shoulder, aiming true.

July 27th, 1803.

A mob of Irish Catholics ask for the password in the Liberties. They line the road with boards of driven nails to stop the cavalry. Kilwarden and the Wolf, returning from a country sojourn without the password, fall to the mob on Thomas street. Their putrid effusions reveal them before the deed, never breathing deeply in enough of the promise of change: Jackeens. Slipping into shadows, insurgents are born. On horseback, on that same fateful night, two English dragoons meet their demise. Clark is grazed for addressing the Lord Lieutenant about his will to sustain Dublin’s loyalty to a despotic English King. And a magistrate walking on Ormond Quay escapes too, lucky to live. Dublin born Irishmen, English partisans who betray their brothers and sisters; who hang the union jack outside their doors, whisper another party line: ‘the attacks must have been personal. It’s an attack on the state, and these deluded wretches must hang’.

Meanwhile, England’s enemies billow the fires in France in response to condescending pens that write of Ireland’s fight for independence: ‘What hope have they now of all the advantages of rational freedom. But their fate had been sealed long before 30,000 pike and 10,000 uniforms are found. Dublin is full of rebels.’

August 25th, 1803.

Rebel leader Robert Emmet, a protestant Irish nobleman who advocates for Irish independence, is captured in Harold’s Cross. He is to be executed for high treason. Defending his good name in the dock, he is allowed to speak, his last words: (sic)

‘I wish my Lordships may suffer it to float down their memories untainted by the foul breath of prejudice, until it finds some more hospitable harbour to shelter it from the storm by which it is at present buffeted.

‘When my spirit shall be wafted to a more friendly port; when my shade shall have joined the bands of those martyred heroes who have shed their blood on the scaffold and in the field, in defence of their country and of virtue, this is my hope, I wish my memory and name may animate those who survive me, while I look down with complacency on the destruction of the perfidious government, which upholds its domination by blasphemy of the most high—which displays its power over man as over his brother, and lifts his hand in the name of God against the throat of his fellow who believes or doubts a little more or a little less the government standard—a government which is steeled to barbarity by the cries of the orphans and the tears of the widows which it has made.

‘I confidently and assuredly hope the wild and chimerical as it may appear, there is still union and strength in Ireland to accomplish the noblest of enterprise—of this, I speak with the confidence of intimate knowledge, and with the consolation that appertains to that confidence. Think not my Lord, I say this for the petty gratification of giving you a transitory uneasiness…

‘Yes my Lords, a man who does not wish to have his epitaph written, until his country is liberated, will not have a weapon in the power of envy to impeach the probity which he means to preserve, even in the grave to which tyranny consigns him.

‘Again I say, that what I have spoken, was not intended for your lordship, whose situation I commiserate rather than envy—my expressions were for my countrymen; if there is a true Irishman present, let my last words cheer him in the hour of his affliction.’

Lord Norbury says he does not sit to hear treason.

Robert Emmet asks, in the courts’ infinite wisdom, where is clemency for an unfortunate prisoner whom their policies do not serve.

‘My Lords, it may be part of the system of angry justice, to bow a man’s mind by humiliation to the purposed ignominy of the scaffold.’

Emmet proclaims his loves and vindicates his character and calls the court a farce. He is interrupted and told to listen to the sentence of the law. Whereupon he asks why the whole ceremony not be dispensed with since sentence was already pronounced before their jury was impaneled calling his lordships ‘Priests of the oracle’.

He is allowed to proceed.

‘I am charged with being an emissary of France! An emissary of France! And for what end? Is it alleged that I wished to sell the independence of my country! And for what end? Was this the object of my ambition? And is this the mode by which a tribunal of justice reconciles contradictions? No, I am an emissary—and my ambition was to hold a place among the deliverers of my country, not in power, nor in profit, but in the glory of the achievement! Sell my country’s independence to France! And for what? Was it for a change of masters? No! But for ambition! O my country, was it personal ambition that could influence me, had it been the soul of my actions, could I not by my education and fortune, by the rank and consideration of my family have placed myself amongst the proudest of my oppressor?

‘My country was my idol; to it I sacrifice every selfish, every endearing sentiment; and for it I now offer up my life. O God! No, my Lord, I acted as an Irishman determined on delivering my country from the yoke of a foreign and unrelenting tyranny, and from the more galling yoke of a domestic faction, which it is joint partner and perpetrator in the patricide of the ignominy of existing with an exterior of splendor and a conscious depravity. It was the wish of my heart to extricate my country from this doubly riveted despotism.

‘My Lords—you are impatient for the sacrifice—the blood which you seek is not congealed by the artificial terrors which surround your victim, it circulates warmly and unruffled through the channels which God created for noble purposes so grievous, they cry to heaven—be ye patient! I have but a few more words to say—

‘I am going to my cold and silent grave: my lamp of life is nearly extinguished: my race is run: the grave opens to receive me, and I sink into its bosom! I have but one request to make at my departure from this world, it is the charity of its silence!—Let no man write my epitaph, for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not the prejudice or ignorance asperse them. Let them and me repose in obscurity and peace, and my tomb remain uninscribed, until other times, and other men, can do justice to my character;—when my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then—and not till then—let my epitaph be written—I have done.’

September 20th, 1803.

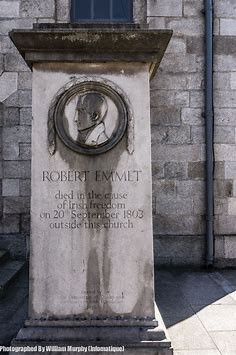

Not far from the Liberties, in front of St. Catherine’s Church, the Irish patriot Robert Emmet is led to the scaffold. A noose is place around his neck whereupon he is hanged until dead. Robert Emmet is then beheaded and quartered while his family look on. No-one comes forward to claim his remains. He is to be buried at the back of Kilmainham Gaol. However, a later search finds no remains. To this day there is no grave. We cannot honour his sacrifice and exceptional character. There is only a memorial plaque on Thomas Street where he was executed. He was 25 years old.

(Taken from Robert Emmet’s speech in the dock, using the court journalist’s (American) spelling and punctuation.)

Darran Brennan

Darran Brennan is a musician and the author of Treoir—about an Irish island community thrown into turmoil by the arrival of an African boy and a lecturer’s attempts to rescue him.

Treoir will be available on October 9th, 2020. Read an excerpt here